For the section of poetry and folk tales in Romania, I chose three classic texts. Făt-Frumos din Lacrimă (Prince Charming From the Tear), Povestea lui Harap-Alb (The Story of Harap-Alb), and Miorița (The Little Ewe). These three pieces of literature are famous in their home of Romania, and beyond. They represent an intriguing blend of kinds of stories, as well as all contributing to the “national myth” that constitutes much of Romanian culture to this very day. The first two stories are classic medievalist tales of brave and brash heroes fighting for what they believe is right, and representing the projected strength of Romanian people. They borrow a lot from classic Western European tales of knights and gallantry, while putting a distinct and unique Romanian and Eastern European spin on the archetypical tale. Meanwhile, Miorița is a more folksy and gentle seeming rural tale of a little sheep interacting with peasant farmers and shepherds. While it may seem like a very different kind of piece of literature on the surface to the first two, it still finds a way to connect to the Romanian strength and perseverance, however in a more naturalistic and pastoral kind of way. Taken in conjunction with each other, these three tales blend together to paint a very specific way of how Romanians view themselves, and those around them.

Harap-Alb is a bold fighter in the Romanian mythology. The eldest son of an “Old King,” he is immediately portrayed in the tale as a competent and masculine figure, ready to take on and fight the perils of his land. At the time this story was written, Romania was trying to stake its own claim as a country and in conflict with numerous neighbours, mainly the Ottomans and other Central and Eastern European nations. Harap-Alb as a heroic figure represents this fight, and shows the strength and resilience that Romania needed to develop as a nation in a time that many groups of people were vying for their own national identities and forming nation-states. In a contemporary sense, Harap-Alb continues to be an important figure. In recent years, the story of the tribulations that Harap-Alb went through in his story has even been shown to help young students better understand the physical and political geography of Romania.

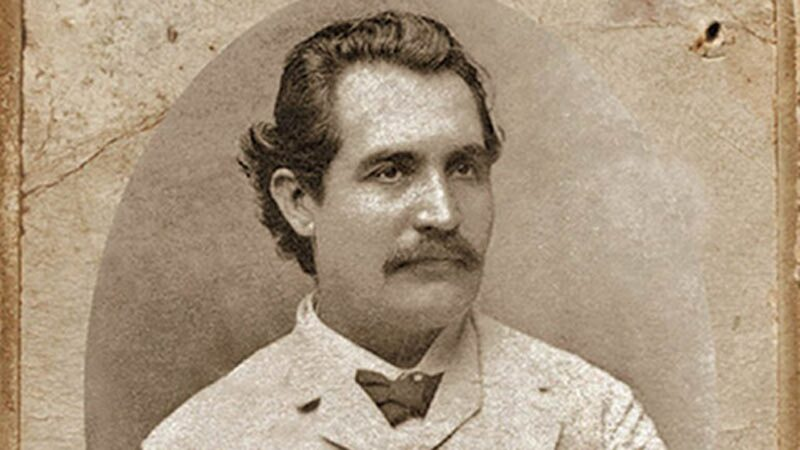

A similar story to Harap-Alb is that of Făt-Frumos din Lacrimă (Prince Charming From the Tear). This is perhaps a more obvious pastiche of Western European mythology, as the name “Prince Charming” is likely already a household name to many children growing up in the west. This Romanian version of the titular hero was born out of a tear from his “mother.” While this character had existed for generations in Romania, it was not until the late 19th century that his story was canonized by the author Mihai Eminescu. Eminescu is a keynote figure in Romanian history, and has been considered to be the country’s equivalent to William Shakespeare. Eminescu is seen to be an extremely conservative and nationalistic figure, with a great distrust for other powers of Europe in his time of the late 19th century. By writing the stories of Prince Charming From the Tear into his own work, Eminescu was projecting the ideals of strength onto his own burgeoning country, and affirming their ideals of national identity and independent separation from those who had tried to conquer them.

The last story covered on my page is Miorița (The Little Ewe). To me, this is the most symbolically interesting and significant tale covered here. While it does not have the bold and adventurous storytelling that the other two stories have, it has what seems to be the deepest metaphorical and symbolic meaning of the ones covered here so far. In it, a farmer is approached by a ewe and told that he will be murdered soon by his fellow agriculturalists. Instead of fighting back and plotting his own scheme to subvert this prophecy, he instead realizes that it is his duty to succumb to fate and become one with the land and natural landscape he inhabits. The fatalism embodied in this story does not represent conflict, like the two prior stories have. Instead, it shows a deep devotion and connection to one’s land, the land that constitutes their country.

Bibliography

Babuts, Nicolae. “A Metaphoric Intercession in Miorita and the Arges Monastery.” Philologica Jassyensia 21, no. 1 (2015): 15-31. http://proxy.lib.sfu.ca/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/metaphoric-intercession-miorita-arges-monastery/docview/1723107376/se-2.

Conţiu, A., Conţiu, H.-V. & Toderaş, A. (2022). Analysis of Geographical

Representations Formed on the Basis of Literary Texts. Romanian Review of Geographical Education, 11(1), 51-72. DOI: 10.24193/RRGE120224

Preda, Adrian Eugen. 2023. “The Conservative Vision Of Mihai Eminescu.” Analele Universitǎti̧i “Constantin Brâncuşi” Din Târgu Jiu. Serie Litere Și Ştiinţe Sociale, no. 1 Supp: 67–74.